Coca‑Cola Red on the Silver Screen

Exploring the Brand's Role in Movies

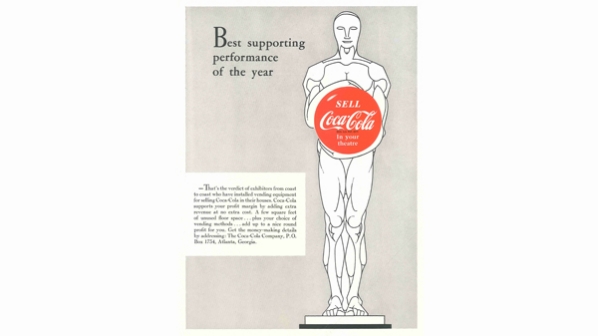

And the best supporting actor award goes to…Coca‑Cola.

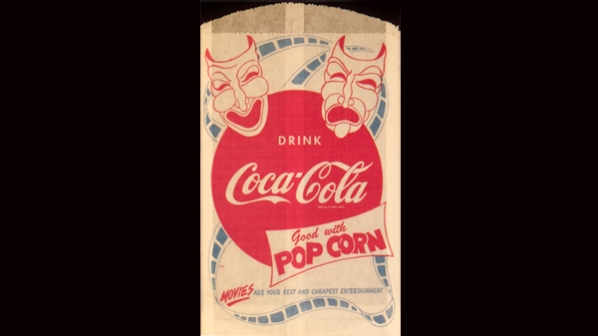

The beloved beverage has held a recurring role in movies through the years, from silent films and foreign flicks, to cult classics, critical favorites and big-budget blockbusters. Coke’s cinematic cameos date back to the early 1900s, continuing through Hollywood’s golden era and beyond.

Coke’s cinematic cameos date back to the early 1900s, continuing through Hollywood’s golden era and beyond.

“From being on the billboard in Times Square in King Kong, to Warren Beatty enjoying the refreshing beverage in Bonnie and Clyde, the influence cannot be denied,” director Ridley Scott wrote in the forward to a new photography book chronicling Coke’s indelible mark on the movie world.

Scott featured a Coca‑Cola neon sign in his 1982 sci-fi thriller, Blade Runner. “The message being,” he explained, “that even in a futuristic dystopian world, Coca‑Cola is everlasting.”

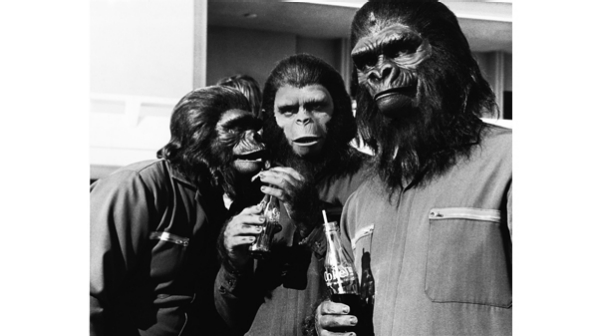

Since Coke has always been a symbol of Americana and a constant fixture in pop culture, the brand has naturally found its way into scripts and onto sets -- not as a scene stealer, per se, but as a subtle part of the narrative.

“Sometimes it’s a Coca‑Cola sign, vending machine or cooler in the background, and sometimes characters are talking about or drinking Coca‑Cola,” said film historian Audrey Kupferberg, who has compiled an extensive list of movies -- and specific scenes -- featuring the brand.

The earliest film to include Coca‑Cola, according to Kupferberg and her husband and creative partner Rob Edelman, is a 1916 silent comedy titled The Mystery of the Leaping Fish. In the cult hit, Douglas Fairbanks is seen driving on a California freeway when he passes by a Coca‑Cola billboard.

“It’s a great example of why Coca‑Cola is in so many movies,” added Kupferberg before rattling off a list of similar scenes. “It’s part of our landscape.”

The Coca‑Cola Company did not initially pursue product placements (several deals were later struck in the ‘20s and ‘30s), likely because it didn’t need to.

“Coca‑Cola’s inclusion in movies has happened organically because filmmakers believed Coca‑Cola truly belonged in the frame,” said Ted Ryan, former Archives director. “When Jimmy Stewart runs down the street in It’s a Wonderful Life, what else would we possibly see in the background but a Coke sign?”

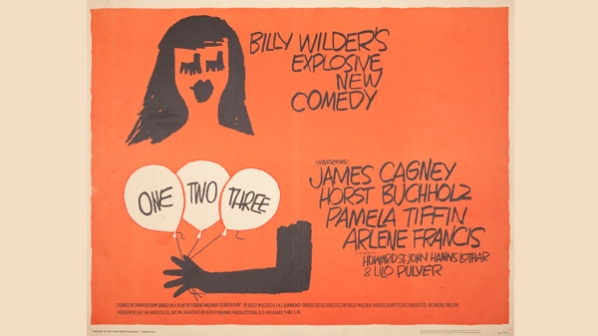

In the 1960s, the company set up an office in Los Angeles to ensure the authenticity of all Coca‑Cola film references. If a studio requested a vintage bottle or sign, for example, the Coke team in Hollywood would provide the items that matched the period and overall aesthetic of the movie.

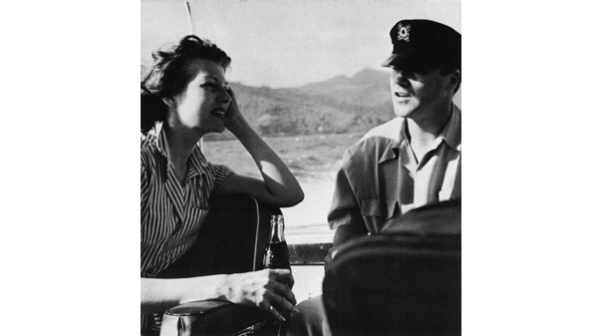

Edelman notes that movies shot on location after World War II provide a historical document of what a particular city -- and, in many cases, a particular brand -- looked like at the time. One of his favorite films, Body and Soul (1947), features a candy store in New York's Lower East Side in the '20s or '30s. "You see images of Coke signs in the windows and inside the store," he said, "so you get a sense of what Coke looked like back then. The production designer thought to put Coke signs in the scene to add a sense of realism."

Some of the brand’s movie roles have been particularly iconic -- including the Coke bottle that falls from the sky in The Gods Must Be Crazy (1980), E.T. (1982) opening can of Coke, Superman (1978) crashing through a billboard, and a vending machine’s appearance in Dr. Strangelove (1964). Others have existed outside the motion picture mainstream.

“In addition to many classics, Coca‑Cola references and visuals have been used in obscure films in interesting ways,” Edelman noted, citing Detour (1945) and Heat Lightning (1934) as examples.

Coke’s filmography also includes more than a few foreign films, a testament to the beverage’s international appeal.

“Our minds are triggered to expect Coca‑Cola in America, but it’s easy to forget the brand is global," Kupferberg says. "In Jean-Luc Godard’s classic 1959 French film, Breathless, Jean Seberg is seen sitting at a Paris café. And what is she drinking? Not wine, but Coke in a contour bottle.”