Honoring a Native Son: Coca‑Cola Exhibit, Panel Pay Tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and His Nobel Peace Prize

01-13-2017

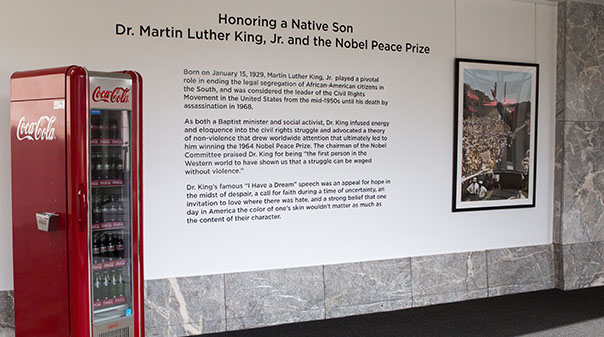

ATLANTA – The Coca‑Cola Company welcomed members of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s inner circle to its global headquarters this week for a conversation about the civil rights leader’s enduring legacy and the role Coca‑Cola played in an Atlanta dinner honoring his 1964 Nobel Peace Prize.

Veteran Atlanta journalist Maria Saporta moderated the panel, which included Dr. Bernice A. King, CEO of The King Center and Dr. King’s youngest daughter; Xernona Clayton, who worked closely with Dr. King and Coretta Scott King in the mid-‘60s through her role at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; and Janice Blumberg, noted author and speaker on American Jewish history.

After Dr. King accepted the Nobel Prize in Norway, a small group of progressive Atlantans organized an interracial, inter-demoninational dinner to honor his achievement and unite the city’s largely segregated communities. One of those leaders was Ms. Blumberg’s late husband, Rabbi Jacob Rothschild.

“The moment we heard the announcement, my husband said to me, ‘The city ought to honor him,” Ms. Blumberg recalled. “But it’s hard for people today to realize how divided the city was. The good news was that one of ours had won the Nobel Peace Prize. The bad news to the great majority of Atlantans, I’m sorry to say, was that it was Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.”

Atlanta had two options: properly recognize the historic achievement, or snub its native son.

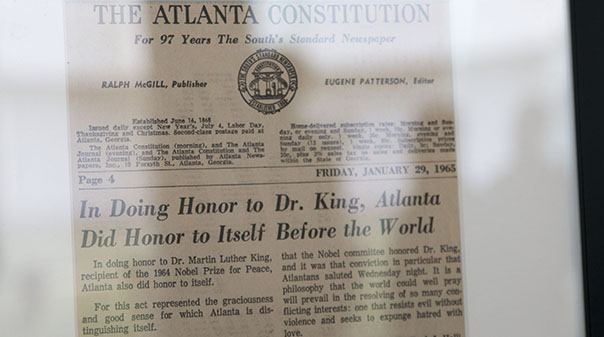

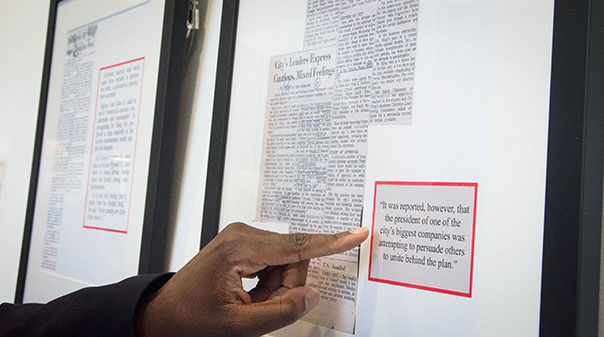

Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr. fully endorsed the dinner from the beginning, but knew that pulling off a high-profile event would require the support of the city’s business elite. Initial invitations to sponsor the dinner were largely ignored, however, inspiring a damning front-page headline in The New York Times: “Tribute to Dr. King Disputed in Atlanta.”

"It’s embarrassing for Coca‑Cola to be located in a city that refuses to honor its Nobel Prize winner,” Austin is quoted as saying that night. “We are an international business. The Coca‑Cola Company does not need Atlanta. You all need to decide whether Atlanta needs the Coca‑Cola Company."

Austin's strongly worded challenge broke through to the group. Within days, all tickets to the dinner were gone.

“(Coca‑Cola) basically put its business on the line to make sure Atlanta responded by honoring Dr. King,” said Saporta, a close childhood friend of the late Yolanda King.

More than 1,500 guests packed the Dinkler Plaza Hotel on Jan. 27, 1965, sitting shoulder to shoulder at long banquet tables. The crowd – most of whom had never broken bread with a member of the opposite race – witnessed an impassioned speech from Dr. King and even broke into an impromptu rendition of “We Shall Overcome.”

“Articles in papers around the nation said, ‘Colored and white people sat and ate together and celebrated this moment… and nothing happened,” said Clayton, who in 1967 became the first African-American to have her own TV talk show and later founded the Trumpet Awards honoring African-American achievement. “It was a glorious moment for Atlanta.”

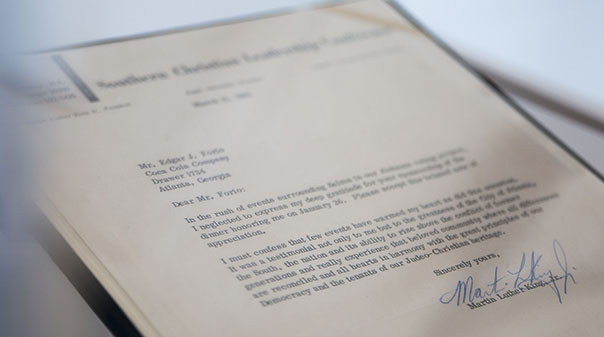

"Few events have warmed my heart as did this occasion. It was a testimonial not only to me but to the greatness of the City of Atlanta, the South, the nation and its ability to rise above the conflict of former generations and really experience that beloved community where all differences are reconciled and all hearts in harmony with the great principles of our Democracy and the tenants of our Judeo-Christian heritage."

“I thank God that Mr. Woodruff, Mayor Allen and others realized how important this moment was,” Dr. Bernice A. King said.

It wasn’t the only time Coca‑Cola stepped up to the plate to back both its hometown and Dr. King. Woodruff was with President Lyndon Johnson on April 4, 1968, the day Dr. King was assassinated. He immediately called Allen to offer the company’s full support to keep Atlanta safe, as violent riots erupted in cities across the country.

“Robert Woodruff saw Atlanta as part of the Coca‑Cola brand,” said Tom Houck, Dr. King’s driver and aide from 1966 to 1968, who attended the panel discussion. “He didn’t want Atlanta to be a Birmingham or a Greensboro. He wanted Atlanta to be Atlanta.”

Clayton added, “We are sitting in the halls of a man who was part of the movement we’re talking about. And Coca‑Cola has never strayed from that. Coca‑Cola was a leader then at a very difficult moment in Atlanta, and here they are still today.”

Photo Credit: Amy Sparks, Hannah Nemer

The panelists toured a new exhibit on the Coca‑Cola campus dedicated to Dr. King and his Nobel Peace Prize. Curated by The Coca‑Cola Company archives in partnership with the Woodruff Libraries at the Atlanta University Center and Emory University, the collection features photographs, letters, newspaper clippings and other artifacts documenting the landmark events of 1964 and 1965, and the intersection of Dr. King’s life with Coca‑Cola.