Delony Sledge's Indelible Mark on Coca‑Cola Advertising

A Genius at Work

09-27-2017

The 130-plus year history of Coca‑Cola was co-written by visionary leaders, fearless innovators, unapologetic mavericks, shameless jokers and – every once in a while – a genius.

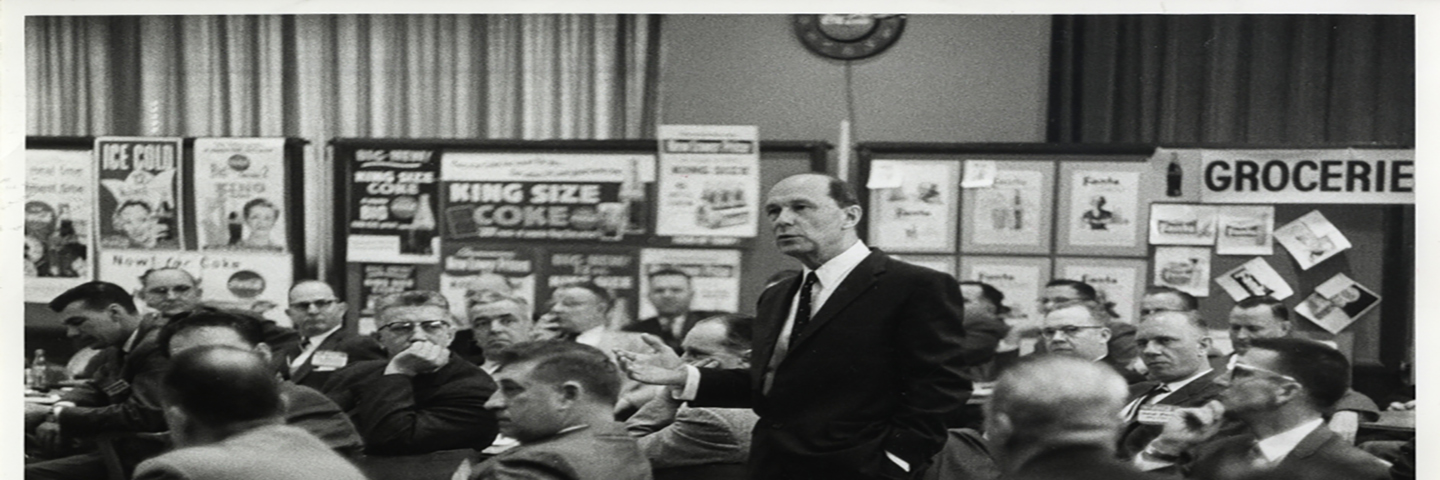

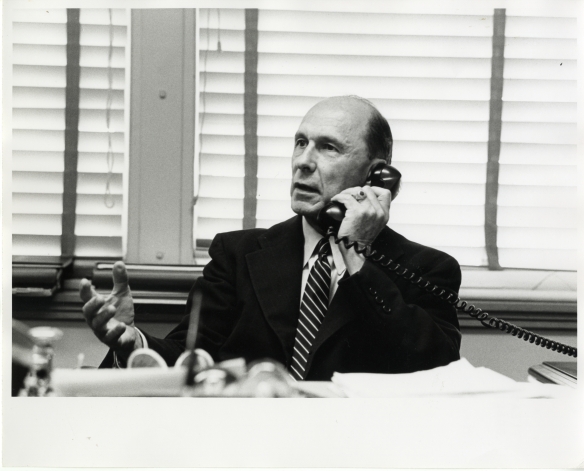

Delony Sledge, one of my favorite characters who ever worked at The Coca‑Cola Company, was was a self-professed, “Genius.” He even had a sign in his office that said “Quiet, Genius at Work.”

That self-effacing mockery fit the character of the humble advertising director born in Athens, Georgia, in 1900. And the irony is even more pronounced when you realize how much Sledge avoided and shunned the spotlight.

Before the era of the Chief Marketing Officer (CMO), Edward Delony Sledge had been responsible for the advertising of the company for nearly 20 years as vice president of advertising when he retired in 1965. He joined Coca‑Cola in 1933 after a varied education and vocational career. He began his studies at the University of Georgia, but only lasted a year before moving to Atlanta to complete two degrees from Georgia Tech.

Well read, a great speaker, classical scholar and huge fan of Shakespeare and drama, Sledge was extremely quick on his feet but was, at the same time, a deep thinker. After graduating college, he served as a ranger at Yosemite National Park, a salesman for the Adair Realty Company, department head at Atlanta Trust Company and finally a salesman at the sign manufacturer, Flexlume Southern, which brought him into contact with Coca‑Cola. Coke recognized a talent and hired him into the advertising department in 1933.

Well read, a great speaker, classical scholar and huge fan of Shakespeare and drama, Sledge was extremely quick on his feet but was, at the same time, a deep thinker.

He was promoted to head of the department in just seven years, but his career was interrupted by military service as he served as a Major in the Coast Artillery Corps after previously serving as a private during WWI. He resumed his career at Coke in 1946, was elected a vice president in 1952 and named director of advertising in 1959.

So why was Sledge important for Coca‑Cola?

Observing his work and his writings, I believe it’s because he thought of both the product and the brand in a different way. He served as a bridge from Robert Woodruff and Archie Lee of D’Arcy Advertising to the change to McCann Erickson in 1956, and did so in a manner that led, rather than dictated, the philosophy of Coca‑Cola advertising.

As background, the two men that were most responsible for Coca‑Cola advertising after 1923 were Woodruff, president of the company, and Archie Lee, the Coke account representative at D’Arcy Advertising. The two bonded quickly, and Woodruff moved the immediate work on the Coca‑Cola account from William D’Arcy to the more junior Lee. They developed slogans like “The Pause that Refreshes,” included artwork by Norman Rockwell and N.C. Wyeth, and in an amazing move, helped with the creation of the modern version of Santa Claus by having Haddon Sundblom begin to paint the gift giver in 1931. In short order, Coca‑Cola became one of the most effective advertisers in American business.

While much of the credit for Coca‑Cola advertising during this period is given to Lee, Sledge believed he was merely expressing the thoughts of Woodruff who saw the role of advertising as “making people like you,” versus selling a product. Sledge absorbed the thoughts of these two men and when he took the reins of the advertising, put them into practice.

The Philosophy of Coca‑Cola Advertising

In 1956, Sledge spelled out his thoughts on advertising in a printed piece called The Philosophy of Coca‑Cola Advertising. It was divided into eight sections and was a fairly prescriptive how-to document. He with his deep love for the product and the work that had been done for generations of advertisers before he took the reins. At the core of all advertising, Sledge continued to echo Woodruff’s earlier refrain noting that his philosophy about our advertising should “be a rational explanation of how to create in the public’s mind a favorable attitude toward Coca‑Cola.” Essentially simple in its phrasing, Sledge’s document offered tremendous insights in how to recruit and retain fans of the brand.

I think the best way to discover the genius of Delony Sledge is through his own words and stories. I am fortunate to have a file in the Archives devoted to Sledge and his writings. Here are a few quotes and interview excerpts that speak for themselves.

The Power of Presence

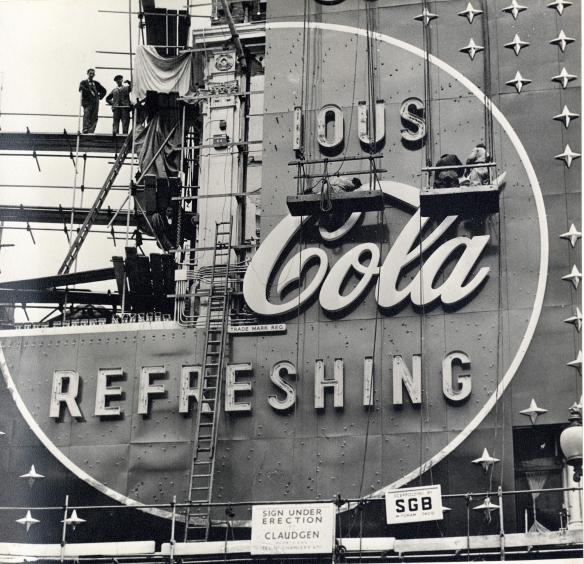

In 1959, J. Paul Austin, then president of The Coca‑Cola Export Company (at the time a separate company and later the CEO of The Coca‑Cola Company) wrote Sledge seeking advice on Coke’s signature sign at Piccadilly Circus. The specular sign was expensive, and Austin wanted Sledge’s opinion on whether was worth the expense.

His reply has been passed down for through generations of Coca‑Cola marketers and the original letter in the Austin collection has the hand-written annotation “Sledge Classic,” scrawled across the top.

Paul,

Before I get through, you will be thoroughly bored with my "philosophy," but your question cannot be answered with a simple "Yes" or "No." Even so, I will attempt to be succinct. If, in my brevity, I appear a little elementary, I pray your indulgence.

I think it would be perfectly fair to say that any ordinary person is one who does ordinary thing is an ordinary way, and that an extraordinary person is one who does extraordinary things in and extraordinary way. If we, in presenting Coca‑Cola to our consumers, are content to do ordinary things in an ordinary way, we must of necessity be content to become, and remain, an ordinary product. If, on the other hand, we determine to do extraordinary things in an extraordinary way, we are perfectly safe in assuming that we will create, in the minds of our consumers, an image of an extraordinary product. Many years ago in the United States, Coca‑Cola chose the latter route, and I believe the character and prestige enjoyed today (and maintained even in the fact of fiercest competition) is the result of this choice.

There is no royal road to prestige. It is a narrow, hard and costly one and the results are not quickly apparent. A man develops his personality traits only over a lifetime of living. A product develops its personality traits just about as slowly, but, once they are developed, it takes just about as long to undevlop them and the more or less impregnable position is worth the cost of scaling the heights.

I am not being nearly specific enough. I will try again: I would not, by any far stretch of the imagination, do away with the Piccadilly Circus sign. I am sure that it has added to the extraordinary quality of Coca‑Cola all over the world. Certainly, it has in the United States. It is costly, of course, but it is worth the money.

Needless to say, J. Paul Austin retained the expensive and prestigious rights to the sign at Piccadilly Circus and it is still there today. These are just a few quotes from a three-page letter, but they begin to underscore Sledge’s philosophy which is that a product is more than a product.

The Taste of Coca‑Cola

When I conducted an oral history interview with Bill Backer, the longtime McCann Coke account lead who wrote “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke,” he described Sledge as one of the best advertisers who ever lived, an opinion shared by Advertising Age and other publications. Backer said Sledge understood the essence of the brand and was willing to act. Bill also recounted the story of how he tried to describe the taste of Coca‑Cola in his book, The Care and Feeding of Ideas. Backer wrote,

‘Like every writer who had ever worked on the Coca‑Cola account, I wanted to try my hand at describing the taste of Coke. Delony had not requested a script of that nature. I wrote it on my own – and found occasion to read it to him alone in the vacant boardroom after and official meeting had disbanded. When I had finished, he sat for what seemed like forever and then said, “William Faulkner tried to describe this product. So did James Dickey (the author of Deliverance.) So have many of your peers over the years. I don’t think it can be done. I don’t think the words exist. What suffices for me is for you to understand that the taste of Coca‑Cola is the greatest taste ever invented by man” - by now Delony was on his feet standing next to the boardroom door- “or God, either, for that matter.” Exit Sledge. End of scene.’

Sledge did indeed exit, but only on his own terms. As noted, for years, he had had a sign behind his desk that read “Quiet, Genius at work.” Over time, he had become playful with the sign and as he left for his World War II service, changed the sign to read “Quiet, Genius at War.” As his 65th birthday approached, Sledge not only avoided all potential retirement festivities, but even kept the fact he was leaving secret to everyone but his supervisors.

On his 65th birthday, McCann Erickson hired a plane to fly around Atlanta wishing Sledge a happy 65th birthday. Shortly thereafter, Sledge worked a full day, making sure he was the last to leave the office took his sign and modified it to say, “Quiet, Genius out to pasture.”

He never set foot in the office again.