How Coca‑Cola Scholar Nathan Alexander is Creating Social Justice Through Mathematics

When Empathy Goes Viral

04-04-2019

Viral Kindness

A few weeks ago, social media buzzed with a photo of a male math professor teaching with an adorable baby strapped to his chest. The photo, snapped and Tweeted by a student in the class, was retweeted 81,764 times, liked 332,503 times, and featured by the Washington Post, CNN and even Oprah Winfrey. To some, a professor holding a student’s baby in class, or even allowing one in the first place, is pretty unusual. But not for 2003 Coca‑Cola Scholar Nathan Alexander, the James King, Jr., Visiting Professor of Mathematics Teaching at Morehouse College.

“As teachers, we find ways to support our students and their learning, and this time was no different. I’m very happy that the world gets to see this moment. More importantly, though, I’m happy that we all get to respect what parents do every single day a little bit more,” Alexander said.

Working to Expand Access to Education

The empathy on display in that viral photo aligns with Alexander's mission to make math and education accessible to everyone.

At Morehouse, he works with first-year students who have had poor experiences with math, developing a community to support and help them boost their grades. He’s also the director of Communicating TEAMS (Communicating by Thinking Effectively in and About Mathematics), a new campus initiative that teaches students to improve their communication skills using mathematics.

On top of that, Alexander makes a state-wide impact as the Georgia State Director for a STEM Teaching Fellowship funded by the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship and Robert W. Woodruff Foundations, supporting prospective secondary teachers with backgrounds in mathematics and science so they can teach in high-need Georgia secondary schools.

Innovative Solutions

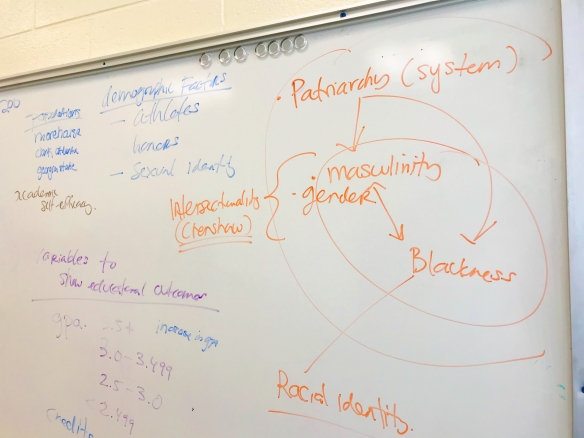

In some related work, he is investigating obstacles to learning mathematics and working with faculty members to help craft innovative solutions for students. Recently,he published a paper in the PRIMUS journal that connects mathematics and social justice. He and two colleagues developed a model for mathematics faculty to engage in difficult conversations about topics related to social, economic and racial justice.

“I wouldn’t be the person I am today without the Coca‑Cola Scholars Program. I don’t say that lightly.

“Most people think of mathematics as this thing that simply solves problems most people are not interested in –something that only astrophysicists or people that work at NASA do,” Alexander said. “People, to no fault of their own, create this self-construction of their mathematical selves they don’t even realize, and this is what we call math identity. So, when I say, ‘Oh, you’re smart and good at math,’ I’m implying that I’m bad at math, and those beliefs are held through time.

“People don’t really say, ‘Oh gosh, that looks like reading. I don’t like reading, I tried those reading classes and I couldn’t do them,’ but we say that about math.”

Bringing Math to the People

To Alexander, the solution is to talk about mathematics in a different way, and to show that math has a social impact for everyone, not just NASA employees.

To explore these realities, he works with high school students in the five-week SMASH (Summer Math and Science Honors) program at Morehouse College, where students engage in advanced science and mathematics courses. “It’s about taking social realities and thinking about quantifying those social realities,” he said. For example, Alexander is working with high school students on the presence of food deserts and gerrymandering, using mathematical modeling to make sense of these problems in the real world.

"In Google Maps, I can type in fast-food restaurants, and they will show up in all different areas,” he said. “Then we can quantify food deserts and why there are more fast-food restaurants and less fresh vegetables in some areas and how they are directly related to socioeconomic status and racial groupings.”

Alexander thinks this mathematical approach to thinking about problems “allows students to really think through the broader applications," he says. "It takes dinner conversations to the classroom and allows us to come together on some things that we already know and feel.”

A Lifelong Passion for Teaching

Alexander had a good deal of teaching experience even before he graduated college. As a double mathematics and sociology major at UNC-Chapel Hill, he kept busy as lead choreographer for his dance group, step master for his fraternity, homecoming king and an enthusiastic tutor in the Math Help Center. But when it came time to graduate, he wasn’t sure what he wanted to do for a career, choosing to pursue a PhD in mathematics and education at Columbia University. In New York, he taught all over the city –Brooklyn, the Bronx, Manhattan –and connected with local Coke Scholar alumni when several attended 1999 Scholar Katori Hall’s 2011 Broadway play, The Mountaintop.

“After the play, we all went to dinner, and as we’re talking, I realize I’m a part of something larger –this woman has a Broadway play, this person has a startup –and I’m a part of this community,” he recalled. “You see other people so deeply invested in something that matters and that they’re good at. There’s a unity, a central purpose. It’s pretty amazing.”

That reconnection in New York brought a realization.

“I wouldn’t be the person I am today without the Coca‑Cola Scholars Program. I don’t say that lightly. I think to take a young person who realizes that they can create positive change and put them around others who have realized that same thing, it’s almost like a catalyst of something –a spark,” he said.

The Value of Community

That spark helped Alexander channel his passions into three distinct areas: teaching, policy and research.

“The question I really am focused on is, ‘How do we change students’ experiences with and perceptions of mathematics in college, but with a specific focus on students who have been historically underrepresented, or really not allowed to learn?’ As an African American, I would have been killed for trying to learn to read and write in the 1600s, and now, on the other end, there are students who can’t read, especially students that look like me. When you add math to that equation, it’s why I’m doing this work,” he said. “It’s about equipping people with the literacy skills and the knowledge and the spaces that they need to get to where they want to go. And when we do that, well, I think we can actually start talking about social justice.”

He’s certainly on his way. He received a grant from ACS (the Associated College of the South) to bring faculty from 16 colleges to Morehouse and Spelman Colleges this summer to learn about teaching social justice in mathematics.

“I hope we can all share what we think is useful about our practices and create some social justice activities to go along with them. I think once we do that, the social movement begins,” said Alexander Nathan.

Oprah, get your Instagram ready.